Student behaviour: beyond “good” or “bad” – towards a Stronger, Smarter identity

Today we’re diving into a powerful idea from Dr Chris Sarra’s doctoral thesis [1] that challenges how we think about student behaviour and identity. Sarra’s thesis is based on the Critical Realist Philosophy which proposes that reality is structured in layers and what we observe is influenced by underlying structures and deep causal mechanisms. Much of this work comes from the famous philosopher, the late Roy Bhaskar. Sarra’s thesis was examined by Roy Bhaskar, and received great praise, especially in the UK, for its creative application of the Critical Realist Philosophy to the topic of Indigenous Education.

Sarra writes in his thesis about a challenge he faced at Cherbourg State School. He argues that behaviours that students might see as resistance don’t actually challenge the system, they mirror it.

One of the problems that we grappled with constantly at Cherbourg is the type of behaviour that lives up to and reinforces mainstream white perceptions of Aborigines. There is a danger that this behaviour can be romanticised as ‘resistance’. Far from being an example of resistance I would argue that behaviour such as vandalism, glue sniffing, or truancy is anything but truly rebellious.

Three Ways Students Respond to Expectations

To explore this further, Sarra draws on the work of French philosopher Michel Pêcheux, who described three ways people respond to the rules and expectations placed on them:

- Identification – The student follows the rules, fits in, and is rewarded. They’re seen as a “good” subject.

- Counter-Identification – The student rejects the rules, misbehaves, and causes disruption. They’re labelled a “bad” subject.

- Disidentification – The student steps outside the whole “good vs bad” dynamic. They build a self-affirming identity that doesn’t rely on either compliance or rebellion.

Sarra explains that while good and bad may seem like they are in opposition to each other, they are actually two sides of the same coin. Even when a student rebels, they’re still reacting to the system and therefore confirming the system.

Sarra explains this quoting Ron Strickland [2]

‘the ‘bad’ subject … simply denies and opposes the dominant ideology, and in so doing inadvertently confirms the power of the dominant ideology by accepting the “evidentness of meaning” upon which it rests’.

In Bhaskarian terms, counter-identification is an instance of ‘dialectical counterparts or contraries’ where we have phenomena which while apparently in opposition, are mutually complicit in that they share a common ground [3] (Bhaskar, 1993: 11 ).

In the third position of disidentification, the student steps outside the system, choosing a different path to either compliance or opposition. This is about cultivating an identity which is self-affirming and independent of the processes of identification and counter-identification.

Identification and Counter-Identification

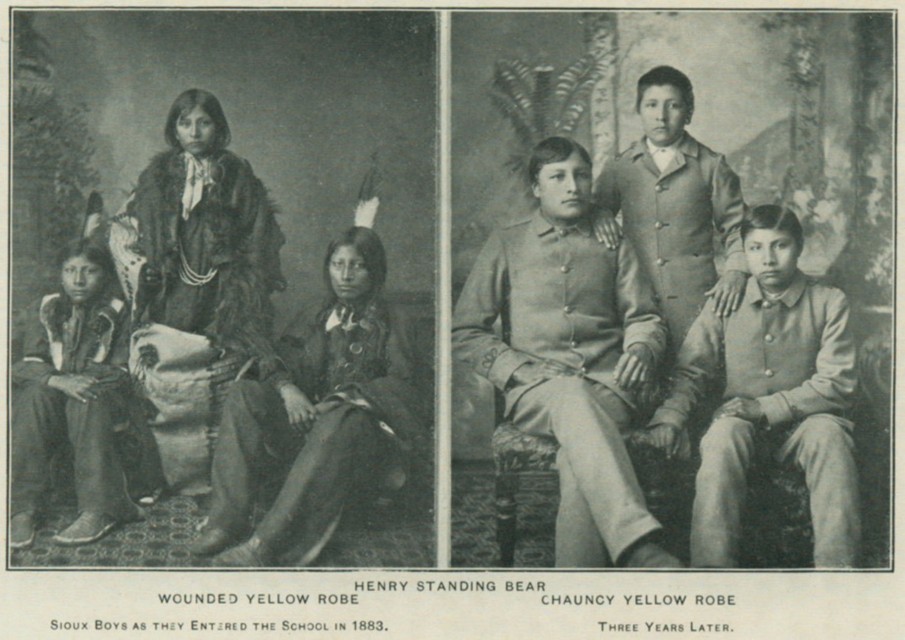

To understand how the “good vs bad” dynamic has impacted First Nations people, we can look at past policies. A well-known example from the United States is the Carlisle Indian School, founded in 1879 [4] . Its goal was to erase Indigenous identity. Captain Pratt, the founder, famously said, “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

When the Indian children arrived at his school, Pratt viewed them as “bad subjects” who should be turned into “good subjects” by eliminating their Indigeneity. He changed their clothing, banned native languages and cut the hair of the male students. He took before and after photos of the students and celebrated them as examples of the march of ‘civilisation’ and the victory of the Settlers over the Indigenous people [5]. The system was rewarding compliance, but at a huge cost to identity and dignity.

The ‘before’ photo of the ‘bad’ subjects arriving at Carlisle Indian school.

The before and after photos from Carlisle Indian School.

In Australia, historical policies have been similar. Missions across the country sought to turn First Nations children into “good subjects” and ‘civilise’ children through schooling. Dr Grace Sarra in her paper on the historical context of Cherbourg State School [6] describes how, when the Barrambah settlement was established at Cherbourg, a key objective was to control and discipline, and to destroy Aboriginal cultural identity which was seen as inferior. At this time, the school aimed to reproduce these dominant values of society: the purpose of schooling was assimilation.

While schooling in Australia has evolved, the dominant Western education system and its norms are still widely used as the standard. It is worth reflecting on how this may continue to subtly reinforce assimilation rather than celebrating diversity. In this situation, student behaviour may be Counter-Identification as students rebel against a system that they don’t see as representing their culture.

Disidentification

In 2024, Oji-Cree actor D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai made a powerful statement at the Emmy Awards by wearing a red handprint over his mouth as a symbol of solidarity with the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement [7].

We can also think back to the 2000 Olympics when Cathy Freeman famously wrapped herself in the Aboriginal flag as well as the Australian flag in a powerful gesture that represented unity and pride for her heritage.

We can also think back to the 2000 Olympics when Cathy Freeman famously wrapped herself in the Aboriginal flag as well as the Australian flag in a powerful gesture that represented unity and pride for her heritage.

These examples are disidentification in action. Rather than trying to rebel against the system, they were standing strong in their own truth and using their platforms to speak out and honour their people and their culture.

Strong and Smart: A Self-Affirming Identity

In his thesis, Sarra reflects on how the Pêcheux model can help in understanding how to build self-affirming identities for students. He describes how in Pêcheux’s terms, truancy is seen as Counter-Identification that simply reinforces stereotypes.

The truant does not challenge the power relations that set up the colonial system. Actually, as my research shows, the truant reinforces white perceptions about Aboriginal behaviour. Aboriginal truancy is no threat at all to white supremacy. What would threaten colonial power relations is for the Aboriginal child to come to school and to do the hard yards to become strong and smart [8] .

As Dr Sarra explains, Disidentification provides an alternative. When students show up, work hard, and succeed, they can contribute to transforming society into one where everyone can flourish. This is the heart of the Strong and Smart identity. This is a self-affirming identity that goes beyond the notions of “good” and “bad” that have historically been defined by our Western schooling system to build an identity for First Nations students that is proud, capable and culturally grounded.

Sarra explained this in further his 2016 NAIDOC speech.

For 50,000 history-making years, our old people lived like kings in lands where camels die of thirst. They stood as ironbark – upright, strong, tall, standing and unbreakable. Their lessons, their songlines, their legacy and their dreamings. They are our true north. They are the truth not only of who we were, but who we can be again.

My brothers and sisters, believe me when I say this.We are stronger than we believe. And smarter than we know.

Solidly anchored by an honourable past, more than any other human beings on the planet, we can take our place in an honourable future. We have survived – and now we must thrive [9].

So What Can We Do as Teachers?

In an education system that is still based on Western standards, Strong and Smart is essential to affirm identity, challenge low expectations, ensure that First Nations are proud and confident. The Stronger Smarter Approach encourages educators to

- Look beyond “good” and “bad” behaviour – ask what’s driving that behaviour.

- Support students to build Strong and Smart self-affirming identities – embed identity-affirming practices across the school.

- Challenge stereotypes and low expectations – encourage critical conversations about unconscious bias and the power of high expectations.

Let’s help our students step out of the “good vs bad” dance and into a future where they’re Strong and Smart.

Coming Soon: Keep a watch out for our next blog ‘How they make you feel’.

2026 Program Calendar: Our 2026 Program Calendar is now available. If you know someone who might want to undertake the SSLP, please direct them to our website for more information.

If you are interested in continuing your Stronger Smarter journey please contact us for more options.

Footnotes:

[1] Sarra, C. (2008). Strong and Smart – Towards a Pedagogy for Emancipation. Education for first peoples. Routledge. P.24

[2] Strickland, R. (2012). The Western Marxist Concept of Ideology Critique. VNU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 28 No. 5E p.47-56.

[3] Bhaskar, R. (1993). Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom, London: Verso. ISBN 0-86091-583-2

[4] “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man”: R. H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

[5] Analyzing Before and After Photographs & Exploring Student Files | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

[6] Sarra, G. (2008). Cherbourg State School in Historical Context. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 37, p.108-119. Cherbourg State School in Historical Context | The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education

[7] D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai draws attention to Indigenous women at 2024 Emmys

[8] Sarra, C. (2008). P.26

[9] Chris Sarra: ‘We are stronger than we believe and smarter than we know’, NAIDOC Person of the Year – 2016 — Speakola

This blog crystalised many concepts and notions I have grappled with both as an Aboriginal student in my youth and a member of Australian society as an adult. I feel it our duty and honour as Aboriginal people to take our place as the future leaders in this modern world, although the chain has been broken through various colonial impacts, this chain can only be mended by us. I fear in many instances Aboriginal people consider themselves separate from the greater Australian society, as if embracing it would somehow make us “less black”. But as the first Australians we should never be ashamed of taking our rightful place in society. Not in direct opposition to current practices, which can often reinforce negative stereotypes; but embracing them in a unique way that only the first Australians can.