09/08/2022

Stronger Smarter Institute’s former Chief of Impact, Jesse King, reflects on National Science Week 2022: Glass: More than meets the eye from the perspective of Indigenous STEM Education.

The theme of National Science Week 2022: Glass: More than meets the eye, gave gave me an opportunity to reflect on working in Indigenous STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering or Mathematics) Education. More specifically, what does this theme mean to me as an educator? And more importantly, what does it mean for me as a descendant of the Waanyi people in north-western Queensland? I was able to reflect on the privilege I have had of working with some of Australia’s foremost thinkers in Indigenous STEM. Often, when faced with some STEM example or context, my mind eventually gets to the question: what does this mean to First Nations Peoples of Australia? How have we understood or demonstrated this concept? We can spotlight First Nations Peoples sophisticated ways of knowing, being and doing, to make educational experiences more engaging for everyone. There is often more than meets the eye.

What is a First Nations lens on glass in Australia?

To begin to explore a First Nations perspective on glass there needs to be a bit of prework. Worked (non-natural, manufactured) glass appears around 4500 years ago, centred around the Fertile Crescent region in the Middle East and expands from there to what we know today, through many significant scientific advancements. Similar glass technologies emerge independently in China around 3000 years ago, possessing unique developmental characteristics [1]. Archaeological evidence suggests sophisticated glass technology existed in Sub-Saharan Africa about 1000 years ago [2]. So what is known about First Nations Peoples of Australia’s traditions with glass?

A cursory glance of the available literature would point towards glass being identified by First Nations Peoples of Australia as a raw material that could be processed in the same way as the manufacture of stone tools. The introduction of glass is evidenced in anecdotal reports of trading beads during early contact periods. These reports contribute to the narrative of the time created by Social Darwinism; no wheel, no pottery, no glass, therefore no civilisation. The dominant philosophies of Social Darwinism pervert many of the early descriptions documented by Europeans, that lack an understanding of the sophisticated knowledges held by First Nations Australians. The scientific agenda at the time of colonisation supressed and silenced First Nations Peoples sophisticated and novel processes, techniques and innovations on this continent, honed since time immemorial.

Recognising the potential of glass, through experiences with glass-like materials

First Nations Peoples of Australia were able to recognise the similar properties of manufactured glass and other raw materials that were already being used in material culture. This is explained in the Australian Curriculum: Science Elaboration Teacher Background Information [3].

“Stone tools provide sophisticated examples of material culture that required the confluence of geological, chemical, biological and physical knowledge. The lithic raw materials (stones) were then reduced by percussion techniques into a variety of tools and blades that could be used either for highly specialised or general purposes. First Nations Peoples of Australia relied on, and built upon, an expert level of geological knowledge to help identify which rocks formed the necessary conchoidal (Hertzian) fractures for tool making. Conchoidal or Hertzian fracture is a technical term used to describe the way that brittle materials such as obsidian, flint, quartzite, chert and other minerals break or fracture in the absence of any pre-existing fault lines or planes within the material.” (ACARA, 2019)

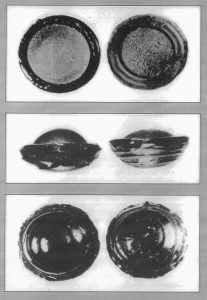

First Nations Peoples of Australia’s recognition, utilisation and contribution to the understanding of australites, is particularly fascinating. Australites are a dark, glossy matter that form a category of tektites[4]. Much has been written about australites from a western perspective. However, I will instead focus on the contribution to the western scientific understanding of australites by First Nations Peoples of Australia.

First Nations Peoples of Australia have many different recorded creation narratives mentioning the extra-terrestrial origins of australites (falling from the sky) [5]. Australites were considered by First Nations Peoples as originating with ancestral beings, and as such, were highly valued. The responsibility for australites was often entrusted to a person of high regard within a community.

There was a particular interest in australites across the Australian continent from the western scientific community. Early western theories attributed the origin of australites to volcanic eruptions. With a bit of imagination, picture the geologists and the First Nations knowledge holder, frustratingly trying to communicate these different world views, across different languages, and both walking away thinking the other didn’t know much about anything.

It wasn’t until the mid-twentieth century, during NASA testing of the impact of atmospheric re-entry on materials, advanced the western understanding of tektite origins. Scientists were able to replicate the creation of a tektite in a wind tunnel. The only reference to First Nation Australians’ long held knowledge about the origin of tektites a one sentence reference describing that when “geologists would ask the Australian Aborigines where the tektites came from they pointed vaguely up to the sky” [6].

Today, our understanding of australites is made possible by analysing the large collections of australites across various museums and private collections. These collections exist because of the exploitation of First Nations Peoples, whose acute vision would result a higher rate of locating australites than non-Indigenous gatherers [7] for which they were often paid with no more than a minty (sweet lolly) [8].

Sharper than steel

First Nations Peoples of Australia manufactured superior cutting instruments from australites that were particularly useful for medical procedures. They were able to apply common knapping techniques to australites to produce blades.

“Although most tools were made from readily available local stones, highly specialised tools and blades made from particular lithic materials (for example, volcanic greenstone and natural glass, such as obsidian and tektites) were traded across extensive distances and used only by highly skilled and knowledgeable people… To this day, no surgical tools have exceeded the efficiency of obsidian blades. There are still some surgeons who use obsidian scalpels as they can cut down to a single micron and leave considerably less scarring as a result. This demonstrates the value of shaping and treating natural occurring materials when compared to modern day manufactured tools, such as surgical steel.” (ACARA, 2019)

With the introduction of manufactured glass to the continent by European colonisers, First Nations Peoples were quick to recognise that the characteristics that make silica-rich stone (obsidian, flint, quartzite, chert etc.) workable are the same that apply to manufactured glass. Evidence of glass being worked by First Nations People exist across multiple archaeological sites such as the Native Mounted Police Camps in Queensland [9], Kempton, Tasmania [10],the Onkaparinga river estuary, South Australia [11], Sydney, New South Wales [12]. Perhaps the most famous examples are Kimberly Points from Western Australia, spear points traditionally manufactured from expert stone knapping techniques, that were later applied to manufacture Kimberly points from glass and porcelain. Essentially, people familiar with fundamental knapping processes react similarly when a new material is presented to them and take advantage of this new resource [13]. This is documented worldwide across all First Nations Peoples where manufactured glass was introduced.

A lens on inclusivity

While glass was not manufactured by First Nations Australians, natural glass–like materials were recognised and utilised for a variety of purposes across the continent. Glass is just one example of cultural technological adaptation First Nations Peoples of Australia successfully incorporated into their repertoire of skills in response to colonisation. The theme of National Science Week 2022: Glass, more than meets the eye gives us an opportunity to consider what glass means from a broad range of cultural and scientific perspectives. As an educator this creates an opportunity to stretch our thinking and create diverse and engaging learning experiences for all students. As a Waanyi person I am proud to be a part of the longest living cultures on earth and have had the opportunity to highlight a small part of First Nations knowledges and their place in National Science Week 2022.

Jesse King

Former Chief of Impact

Stronger Smarter Institute

Footnotes:

[1] Gan, F., Cheng, H., & Li, Q. (2006). Origin of Chinese ancient glasses—study on the earliest Chinese ancient glasses. Science in China Series E: Technological Sciences, 49(6), 701-713.

[2] https://theconversation.com/how-we-found-the-earliest-glass-production-south-of-the-sahara-and-what-it-means-142059

[3] https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/TeacherBackgroundInfo?id=56799

[4] Clarke, P. A. (2018). Australites. Part 1: Aboriginal involvement in their discovery. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 21(2), 115-133.

[5] Clarke, P. A. (2019). Australites. Part 2: Early Aboriginal perception and us7e. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 22(1), 155-178.

[6] Bugos, G. E. (2010). Atmosphere of Freedom: 70 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center (Vol. 4314). National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA History Office.

[7] Baker, G., 1959. Tektites. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria, 23, 5‒313

[8] Fenner, C., 1940. Australites, Part IV. The John Ken-nett collection, with notes on Darwin glass, bedia-sites etc. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 64, 305‒324.

[9] Perston, Y., Wallis, L. A., Burke, H., McLennan, C., Hatte, E., & Barker, B. (2021). Flaked Glass Artifacts from Nineteenth–Century Native Mounted Police Camps in Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 1-34.

[10] Tindale, N. B. 1941 A Tasmanian stone implement made from bottle glass. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania , pp. 1-2; plate 1

[11] Freeman, John A. (Sean) 1993 A Preliminary Analysis of the Glass Artefacts Found on the Onkaparinga River Estuary. Graduate Diploma in Archaeology diss. Flinders University, Adelaide.

[12] Goward, T. (2011). Aboriginal glass artefacts of the Sydney region.

[13] Cooper, Z., & Bowdler, S. (1998). Flaked glass tools from the Andaman Islands and Australia. Asian Perspectives, 74-83.